Carl Erskine: Oisk, Beloved in Brooklyn, Forever

The Brooklyn Dodgers. My all-time favorite sports team.

They were not the greatest baseball club of their most successful era - the late 1940s up until the mid-1950s. The New York Yankees attained that status.

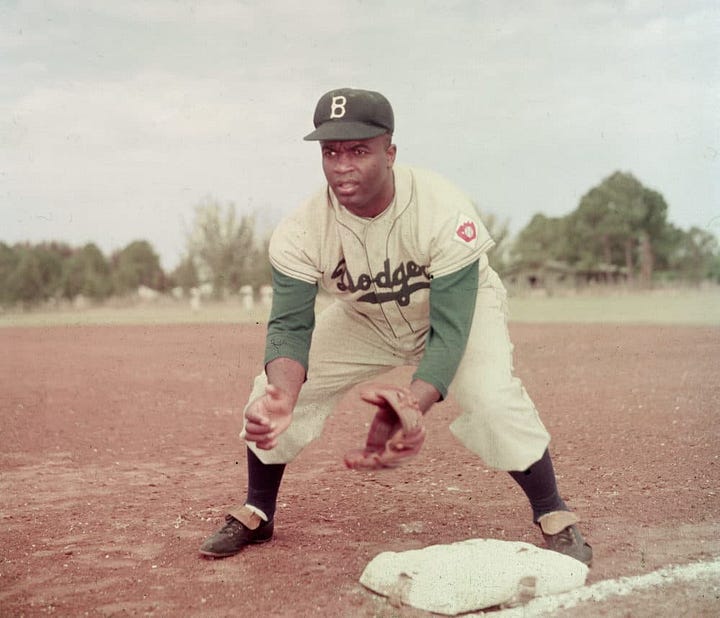

Yet the BROOKLYN Dodgers were the most consequential team in the history of American professional sports. They integrated Major League Baseball with the advent of Jackie Roosevelt Robinson in the Dodgers lineup at first base on Opening Day, April 15, 1947. It all happened at the Dodger ballpark, the late, lamented Ebbets Field, Brooklyn, against the then Boston Braves.

Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. once told Jackie that none of the advances he made on behalf of African Americans would have been possible had it not been for Robinson’s impact on American society. Jackie had broken the seemingly insuperable Jim Crow barrier that had barred Black Americans from Major League Baseball, the National Pastime. His was the ultimate triumph over monumental physical and emotional abuse from white Americans on and off the baseball field.

To put Jackie’s historical achievement in perspective, one must remember the motto of The Sporting News, known as the Bible of Baseball: “Baseball is a game played by Caucasian gentlemen.” Of course, many of these Caucasians were not gentlemen. Remember Enos Slaughter, a racist low-life who spiked Jackie in the heel during that 1947 season. And that bum is in baseball’s Hall of Fame!

The Brooklyn Dodgers were undoubtedly the best National League team of that era, winning pennants in 1947, 1949, 1952, 1953, 1955, and 1956, and their only World Series victory in Brooklyn in 1955. They also had the most fervent and loyal fans in National League history. When Dodger owner Walter O’Malley moved the team from Brooklyn to Los Angeles after the 1957 season, motivated by his greed and desire for a personal land grab, it created a wound in the heart of the good people of Brooklyn that, to this very day, 67 years later, has not yet been completely healed.

Those Dodgers were the subject of the most remarkable sports book ever written, The Boys of Summer, authored by Roger Kahn and published in 1972. Kahn and Pete Hamill, both deceased, remain my two favorite American writers. Both are natives of Brooklyn. Indeed, the endearing quality of Brooklyn is a recurrent theme in their writings.

Brooklyn will always be my favorite place in America. For me, it retains a special magic. Although Brooklyn was merged with Manhattan and the other three boroughs into the City of New York in 1898, known in Brooklyn as “the mistake of ‘98,” it retains an identity as a separate city. It is a borough of unique and incredible ethnic and racial diversity, as well as the differences in styles of housing that distinguish each neighborhood.

I experience a special joy every time I visit Brooklyn. As an American Orthodox Jewish community member, I feel a resurgence of energy when I visit the Jewish neighborhoods of Boro Park, Williamsburg, Crown Heights, and Midwood. Brooklyn has the largest Jewish community outside of Israel, and its continued vibrancy in a rapidly assimilating Jewish Diaspora also reassures observant and proud Jews.

And Brooklyn is in the midst of a major comeback. Its new development, commercial and residential, is remarkable. Most significantly, Brooklyn once again has its own professional sports team, the Brooklyn Nets of the National Basketball Association. When one attends a Brooklyn Nets game at the Barclays Center and hears the crowd cheer “BROOKLYN, BROOKLYN,” he or she can sense the enthusiastic spirit once exhibited by those magnificent Brooklyn Dodger fans.

Indeed, the history of the Brooklyn Dodgers remains ever-present in the Borough of Kings. Like many other surviving fans of “the Beloved Bums,” I visit the Ebbets Field site annually at the corner of Bedford Avenue and Sullivan Place. Now, the location of an aging apartment complex and its memory inspired the Frank Sinatra song, “There Used to be a Ballpark.” And older fans can stand there and remember the Dodger theme song, “Follow the Dodgers,” played by the famous Dodger organist, Gladys Gooding every time the Dodgers emerged from the dugout. They ran onto the tundra of Ebbets Field.

Fans like me visit the grave of Jackie Roosevelt Robinson at the Cypress Hills Cemetery in Brooklyn. It is indeed a baseball holy place.

On April 16, 2024, the last surviving member of the Brooklyn Dodgers profiled in The Boys of Summer, Carl Erskine, passed away at the age of 97. Carl was Jackie Robinson’s closest interracial friend among the Dodger players. He stood with Jackie in his struggles against physical and emotional racist abuse.

Jackie Robinson was the epitome of greatness. And Carl Erskine was the epitome of goodness.

Before we reminisce about Carl Erskine's profound decency, we should not forget that he was an excellent pitcher, one notch below Hall of Fame quality.

In his career with the Dodgers, from 1948 until 1959, “Oisk,” as he was belovedly known in Brooklyn, had a fine lifetime record of 122-78, including a 20-6 season in 1953. He won World Series games in 1952 and 1953, with a World Series record-setting 14 strikeouts in Game 3 in 1953. This record stood until Sandy Koufax broke it in Game 1 of the 1963 World Series with 15 strikeouts against the Yankees. In an era when no-hitters were few and far between, Oisk pitched two no-hitters, one in 1952 and the other in 1956.

There were better pitchers than Carl Erskine, but one would be hard-pressed to find better human beings than Oisk and his surviving wife, Betty. Their story was best recounted in the Indy Star article of April 16, 2024, which eulogized Carl upon his passing.

A native of Anderson, Indiana, once a Ku Klux Klan stronghold, Carl defied the prevailing racism of Indiana in his youth, maintaining a brotherly relationship with an African-American fellow basketball player, Johnny Wilson. Those who knew Carl then were unsurprised that he and Jackie Robinson formed such a powerful bond.

While Carl played with the Dodgers, he and Betty resided in the still family-oriented Brooklyn neighborhood of Bay Ridge, and Carl became a hallowed member of that community. After his baseball career was over, Carl returned to Anderson.

Carl and Betty had an outstanding marriage, with joy from their children. All this was put to the test, however, in 1960, when Betty gave birth to Jimmy, a baby with Down Syndrome. The Erskines were advised to have Jimmy institutionalized.

Carl and Betty refused. They were determined to give Jimmy as usual a life as possible. The average life expectancy of a Down syndrome baby at that time was 10 years.

Defying all expectations, thanks to the superhuman efforts of the Erskines, Jimmy lived to the age of 62, passing away in 2022. He held a job and excelled in the Special Olympics.

Carl and Betty became a national model for what parents can achieve for children with special needs and intellectual disabilities. Oisk became an influential national spokesman for the Special Olympics. Still revered in Brooklyn, he was honored by naming a street off Exit 15 of the Belt Parkway as Erskine Street.

In 2023, Carl Erskine received the Buck O'Neil Lifetime Achievement Award from the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum. This award is presented no more frequently than once every three years. It honors an individual whose extraordinary efforts enhanced baseball's positive impact on society, broadened the game's appeal, and whose character, integrity, and dignity are comparable to the qualities exhibited by O'Neil, the famed first baseman and manager of the Negro League. Carl was a most appropriate honoree.

There are two other important lessons to be learned from the passing of Carl Erskine.

We live in the era of Donald Trump and the Cult of Maga. This cult is basically a white grievance entity that venerates Donald Trump, condoning his misogyny, racism, corruption, and his proven act of rape. Carl Erskine proves that America stands for something much better, a counter-example to the stain and stench of Trump and Trumpism.

The second lesson is the beauty of baseball tradition. As my friend and highly respected Orthodox Rabbi Evan Hoffman of New Rochelle, New York, has noted, baseball is the primary sport where fans pass on stories from “generation to generation.” This is humorous yet warm, similar to the Jewish tradition of passing down observances and customs from “generation to generation,” as translated directly into the Hebrew, “L’Dor Va-Dor.”

As Rabbi Hoffman and his son Ellie, both great Met fans will tell you, baseball truly is “L’Dor Va-Dor!” In jocular fashion, given the large number of Jewish Mets fans, I am suggesting to the Mets that during the 7th inning stretch, the Mets should play this version of the song, “L’Dor Va-Dor!” It would be a fine accompaniment out at Citi Field to the presently played “Take Me Out to the Ballgame” and “Che La Luna Mezzo Mare!”

In a more serious vein, however, the magnificent memory of the Brooklyn Dodgers will always be part of the “L’Dor Va-Dor” tradition in Brooklyn. Carl Erskine will be integral to Brooklyn’s “L’Dor Va-Dor.” Oisk will remain beloved in Brooklyn for eternity and will always be a shining example of what’s good and great about America.

Alan J. Steinberg of Highland Park served as regional administrator of Region 2 EPA during the administration of former President George W. Bush and as executive director of the New Jersey Meadowlands Commission. He is a graduate of Northwestern University and the University of Wisconsin Law School.